Gaming on the Amiga — Part 1: Amiga 500 is all you need (mostly)

Table of contents

Introduction

It appears that the generally accepted “best” way to play Amiga games these days is via WHDLoad on an Amiga 1200 (either emulated or real hardware) expanded to oblivion with a turbo card and lots of extra RAM. I disagree with this notion for a number of important reasons:

- It’s suboptimal

While WHDLoad solves some problems (if you count disk swapping and loading times as such), WHDLoad conversions quite often introduce their own set of significant issues, sometimes making the game overall slower than the original floppy version, or even broken and uncompletable. In many cases, it’s one step forward and two steps back with WHDLoad.

- It’s inauthentic

As I get older, I find myself caring more about the preservation of the original Amiga experience for the future. Even perfect WHDLoad conversions (and many are far from it) take away from that authentic experience. It would be a sad thing indeed if these imperfect WHDLoad conversions were the only surviving artifacts 50 or 100 years from now!

- It’s unnecessary

Depending on what games you enjoy playing, WHDLoad might as well be a completely unnecessary and easily avoidable complication (especially when using an emulator).

Am I being unfairly harsh towards WHDLoad? Well, I don’t think so, and I must add I harbor no ill will towards its authors, nor the creators of the numerous WHDLoad ports. While WHDLoad is certainly a great technical achievement, and it might be your only option if you want to play older games on later Amigas equipped with faster processors and later Kickstart ROMs, it’s simply not the ultimate solution many people make it out to be. While no doubt grabbing some hard drive image pre-installed with all WHDLoad games in the known universe requires the least amount of effort (especially for newcomers who don’t want to learn about the Amiga), it’s not all roses with WHDLoad; it does introduce its own set of problems not present in the original games.

If avoiding disk swapping or reducing loading times are your primary motivations for using it, there are much simpler ways to achieve those goals (especially when using emulation) while completely bypassing the various issues that WHDLoad conversions might introduce. These issues range from mere annoyances to game-breaking bugs which might put Amiga games in a bad light for people new to the platform (how could they tell if some problem is present in the original game or the WHDLoad port is at fault?), and annoy oldtimers like me who are after replicating the Authentic Original Experience™. Most importantly, these issues are not present in the original games! Therefore, that is what we’ll be looking at in this article series—playing Amiga games in their original, unaltered form. That means running the games on the hardware they were intended for, and no cracks, no WHDLoad, no patches—unless absolutely necessary.

Prerequisites

This guide assumes some basic familiarity with the Amiga line of home computers. If you’ve never used one of these magnificent machines before, or if you want to get back into the hobby after several decades without having used one, I highly recommend reading the excellent Amiga Beginner’s Series first. It covers a lot of ground quite succinctly, and if not everything makes complete sense, don’t worry; I’ll explain the important things in more detail later. But you need to understand the basics first, and without a desire to have some basic level of technical understanding of how the Amigas work, you won’t get very far. Personal computers from the 80s and 90s are not consoles; every user (including gamers) was expected to have some minimal knowledge of the hardware to be able to use it effectively.

Another essential thing: Amiga games look wrong without properly emulating a period-correct 15 kHz CRT monitor, so I highly recommend referencing my earlier article on setting up an authentic Commodore 1084S shader for WinUAE before getting started.

A brief history of the Amiga

The first Amiga ever, the iconic Amiga 1000 was released in 1985 to the unsuspecting public, followed by the more budget-oriented Amiga 500 in 1987. These were simply the best home computers money could buy at that time; it was unbelievable—as if someone time-travelled back from the future to bring the world’s first true multimedia computer to us (no, it wasn’t the Macintosh, neither the much later “multimedia Pentium PCs”).

The Amiga 500 featured the same Motorola 68000 processor running at 7.14 MHz, and nearly the same Original Chip Set (OCS) as the Amiga 1000. In Amiga terms, the chipset defines the graphics capabilities of the machine. The OCS chipset was able to display up to 32 colours on the screen out of a palette of 4096 colours (64 in the special Extra Half-Brite (EHB) mode, and all possible colours in Hold-And-Modify (HAM), but this was only utilised in a handful of games).1 The most common screen modes for games were 320×256 (PAL) and 320×200 (NTSC), but some made good use of the 640×256/200 hi-res resolutions as well.

The other important defining characteristic of an Amiga computer is the version of the Kickstart, which is the firmware part of the operating system. This resided in a ROM chip on the Amiga 500 and later models. Kickstart 1.3 was the standard Kickstart for the Amiga 500, but some early models came with version 1.2. Even earlier versions than that were buggy beta releases and thus can be safely ignored.

The Amiga 500 was a tremendous success; it sold several millions of units worldwide (the exact figure is a never-ending point of contention). It should be of little surprise then that the overwhelming majority of the Amiga gaming catalogue was targeting OCS-equipped Amigas with 1 MB of RAM running Kickstart 1.3—in other words, the ubiquitous Amiga 500, the most popular Amiga model ever, with a 512 KB RAM expansion board which was de-facto standard. This is quite understandable, as the relatively low price point of the Amiga 500 made it a very attractive choice for parents wanting to buy a personal computer for their kids (IBM PC compatibles with similar capabilities could easily cost 3 to 5 times more in Europe). And those “similar capabilities” of the PCs haven’t materialised until about 1989 (with some goodwill), the year the Sound Blaster 1.0 was released, and it took a few more years for the VGA adapters (initially released in 1987) to come down in price so ordinary people on regular salaries could afford them (especially outside of the US).

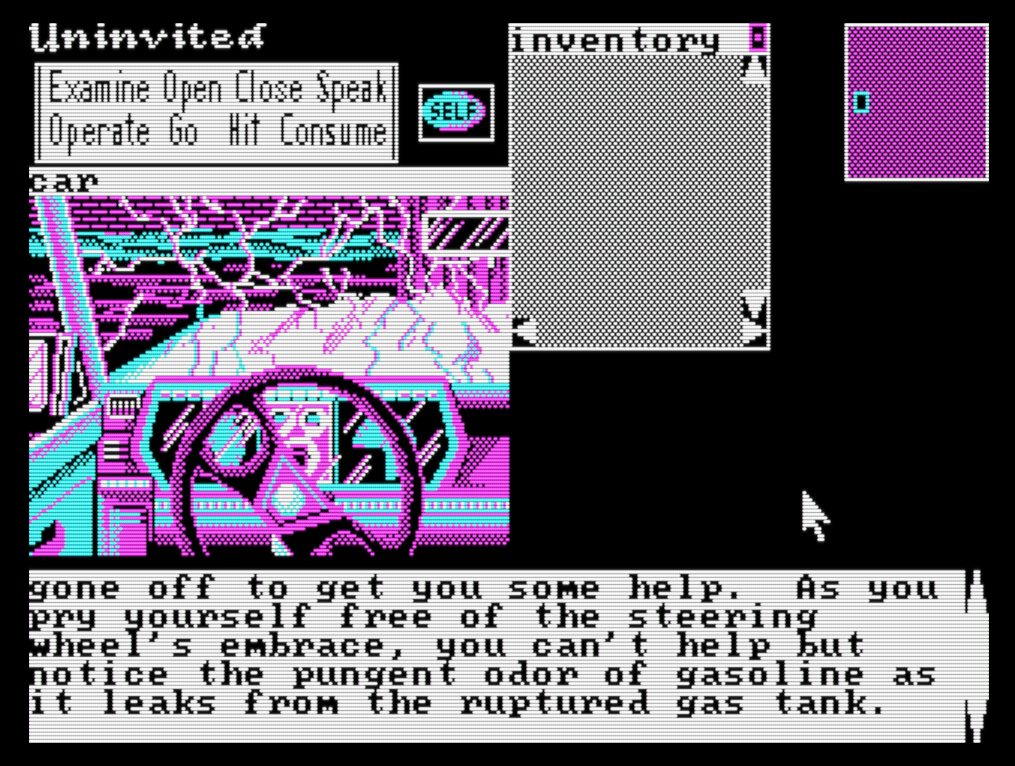

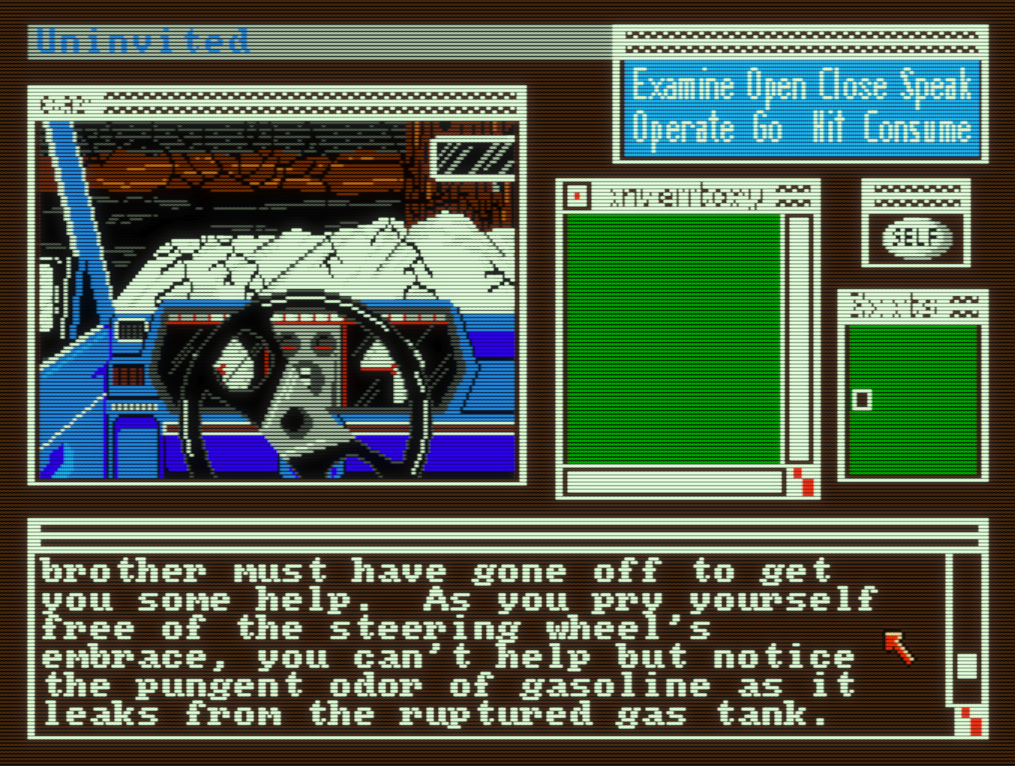

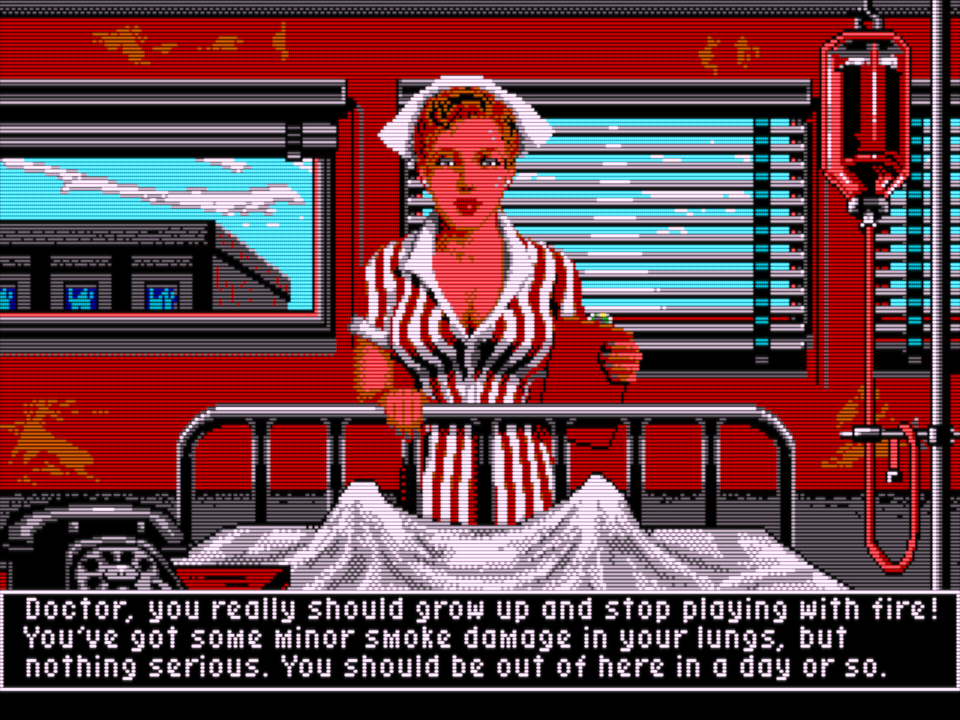

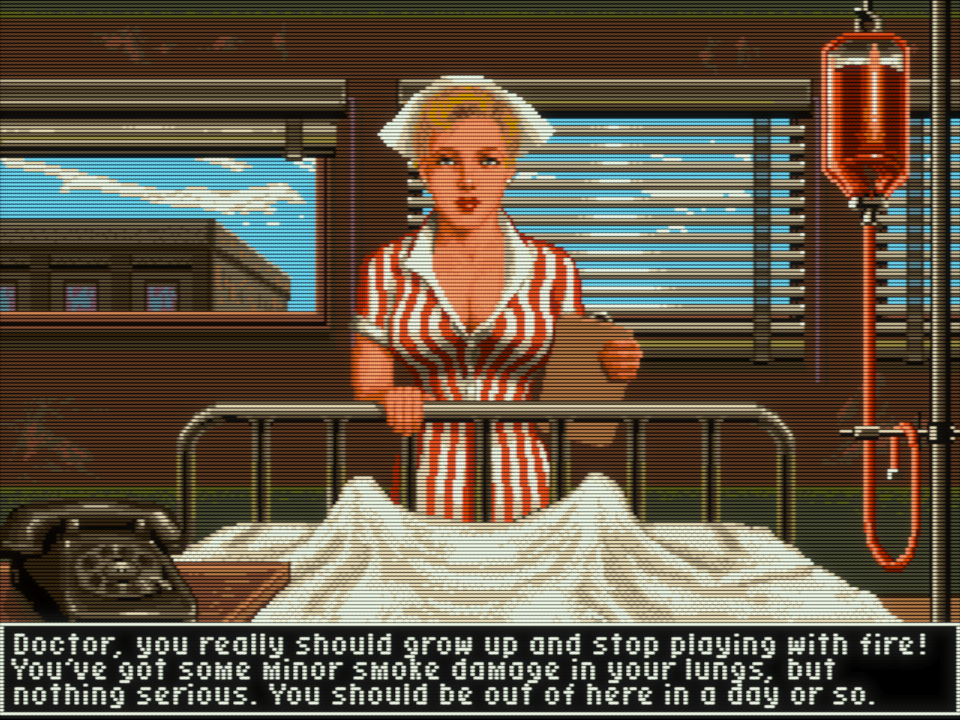

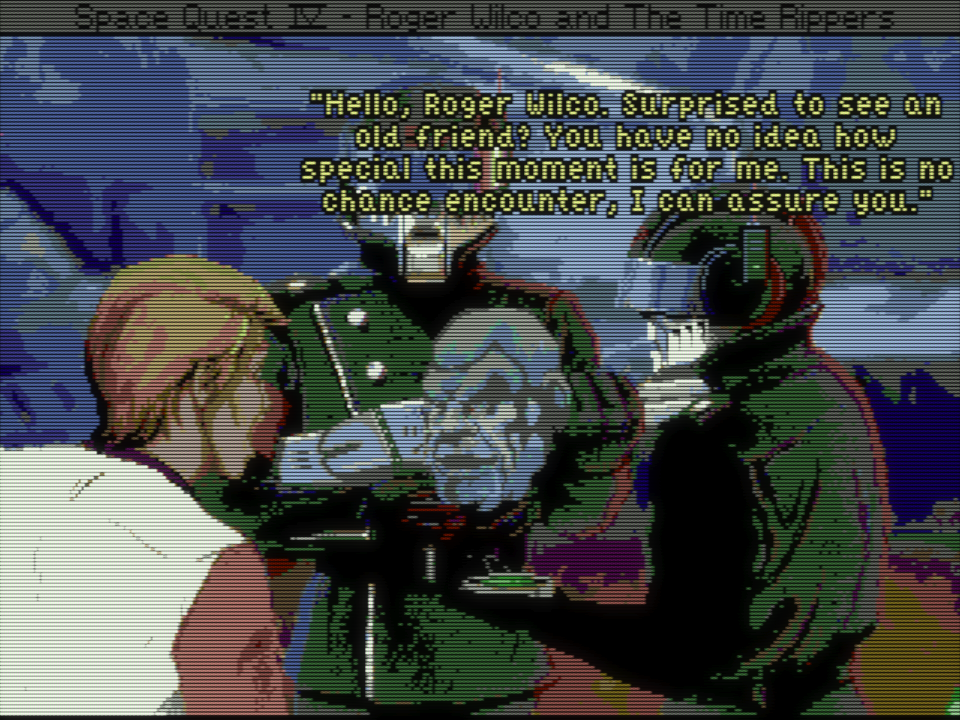

The below comparison screenshots illustrate pretty well the difference between PC and Amiga gaming in the 80s. I clearly remember the vague depressive feeling when friends were trying to impress me with some Hercules or CGA game on their IBM PC compatibles that could only emit weird metallic noises from the PC speaker for “music” (“If this is going to be the future of «serious computing», I’d rather be doing something else…") To put it simply, it’s rather pointless to play most pre-1990 games on DOS if an Amiga (or even Commodore 64!) port also exists—unless for research reasons or due to extremely strong nostalgic feelings towards the crawling horror also known as “CGA graphics.”

The next major chipset generation was the Amiga Advanced Graphics Architecture (AGA) which found its way into the successor of the Amiga 500 in the budget category, the Amiga 1200 released at the end of 1992. It was a rather lackluster incremental upgrade over OCS and the shortlived ECS chipset (which is unimportant from a gaming perspective). At this point, Commodore was basically playing catchup with the IBM PC compatibles. Although AGA made the use of 256 colours out of a total palette of 16 million possible, similar to the VGA standard released in 1987 (note the huge five year gap there!), it was an architectural dead-end. No improvements had been made to the Amiga’s sound capabilities at all (I don’t count the removal of the fixed low-pass filter as an improvement); it was the exact same 4-channel / 8-bit / up to ~28.8kHz audio the Amiga 1000 introduced in 1985. At the same time, 1992 saw the release of landmark PC audio cards such as the Sound Blaster 16 (CD-quality audio, FM synthesis, optional MIDI daughterboard) and the Gravis UltraSound (CD-quality audio, 32 channels, hardware mixer, up to 1 MB of sample RAM). From 1992 onwards, you could no longer proudly recommend Amiga versions of games as the “best” versions; the PC had simply taken over and became the leading platform. Amiga ports had become mostly just afterthoughts, ranging from mediocre to embarassingly bad. With the eventual demise of Commodore in 1994, developers started to abandon the platform in droves, and the fate of the Amiga as a mainstream gaming platform was sealed. Some might argue that the final nail in the coffin was the release of Doom a bit earlier in 1993, establishing the hugely popular FPS genre. It was simply impossible to achieve a similarly fast-paced 3D gameplay on a stock Amiga 1200 with the AGA chipset. Regardless of the significance of Doom in the downfall of the Amiga, the new line of machines could not keep up with the fast advancements in the 3D graphics arena, and at that time 3D was what most gamers wanted.

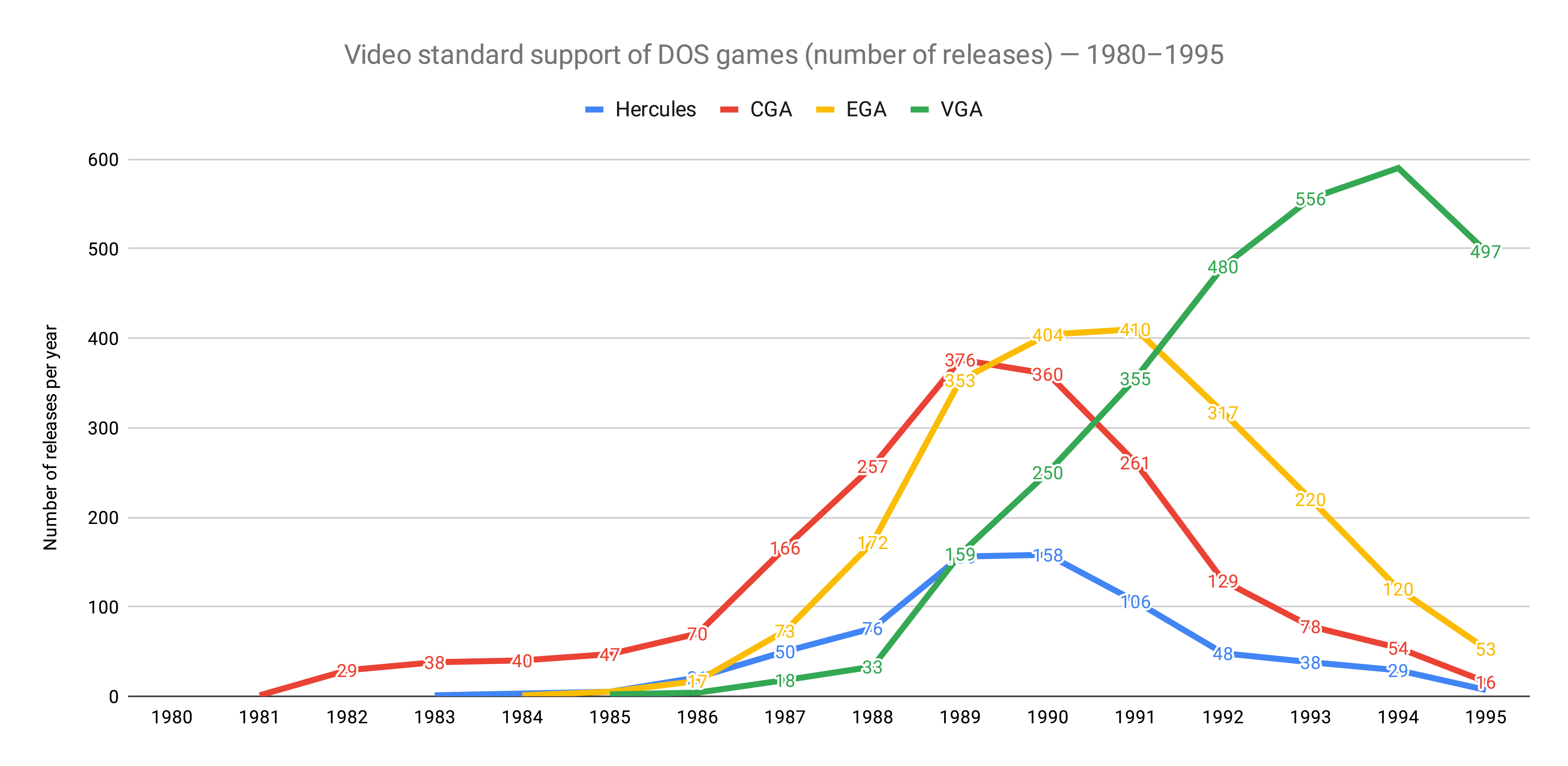

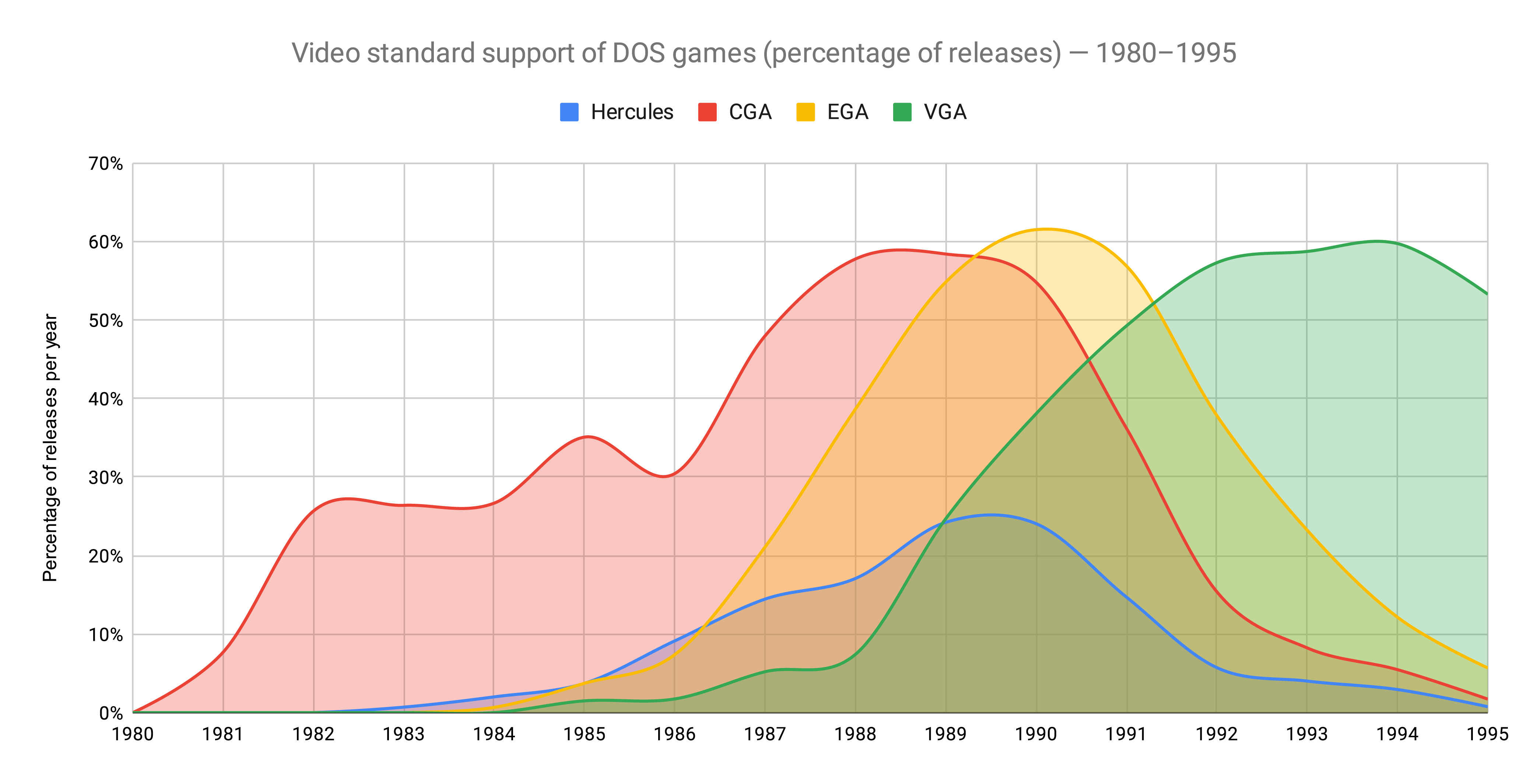

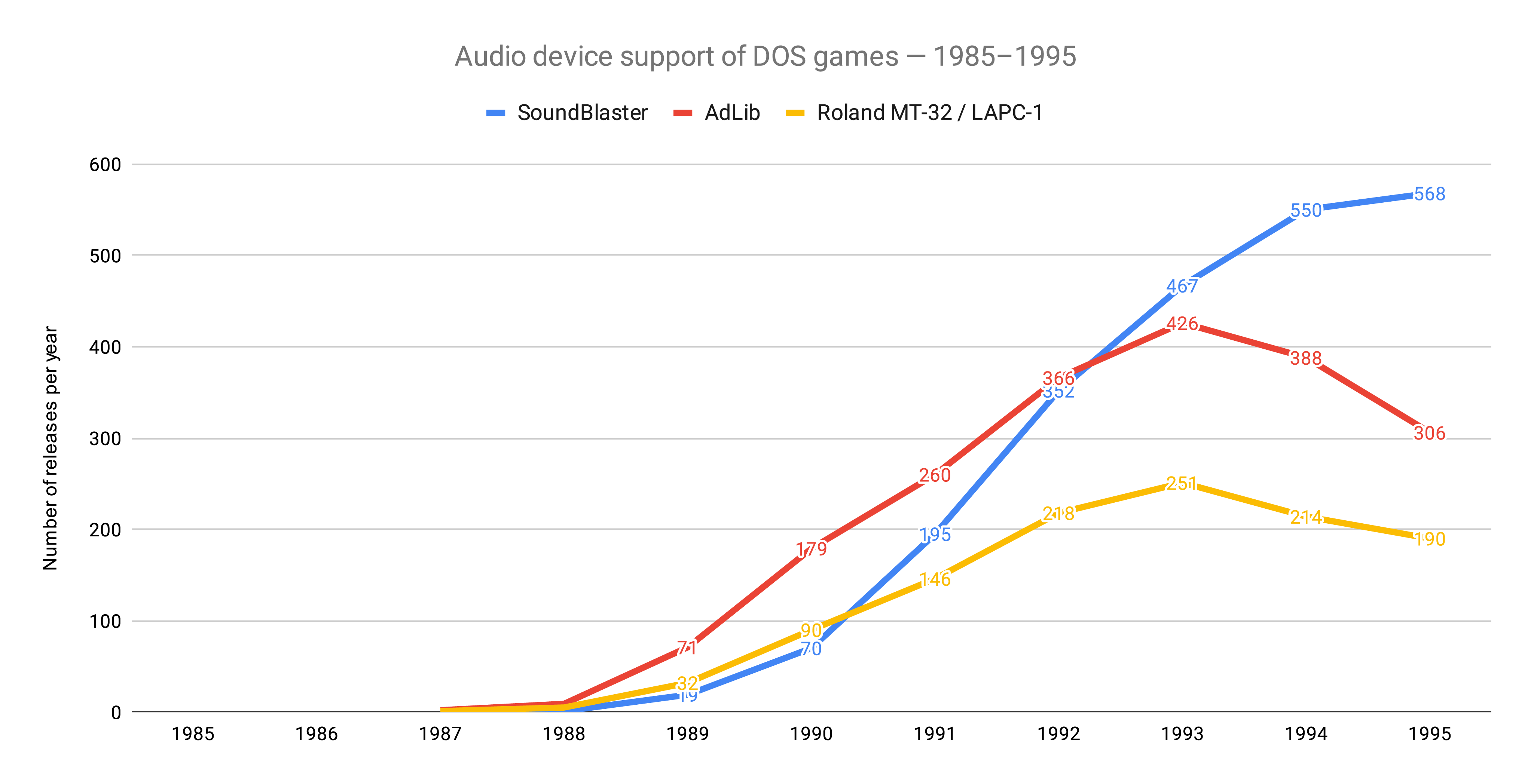

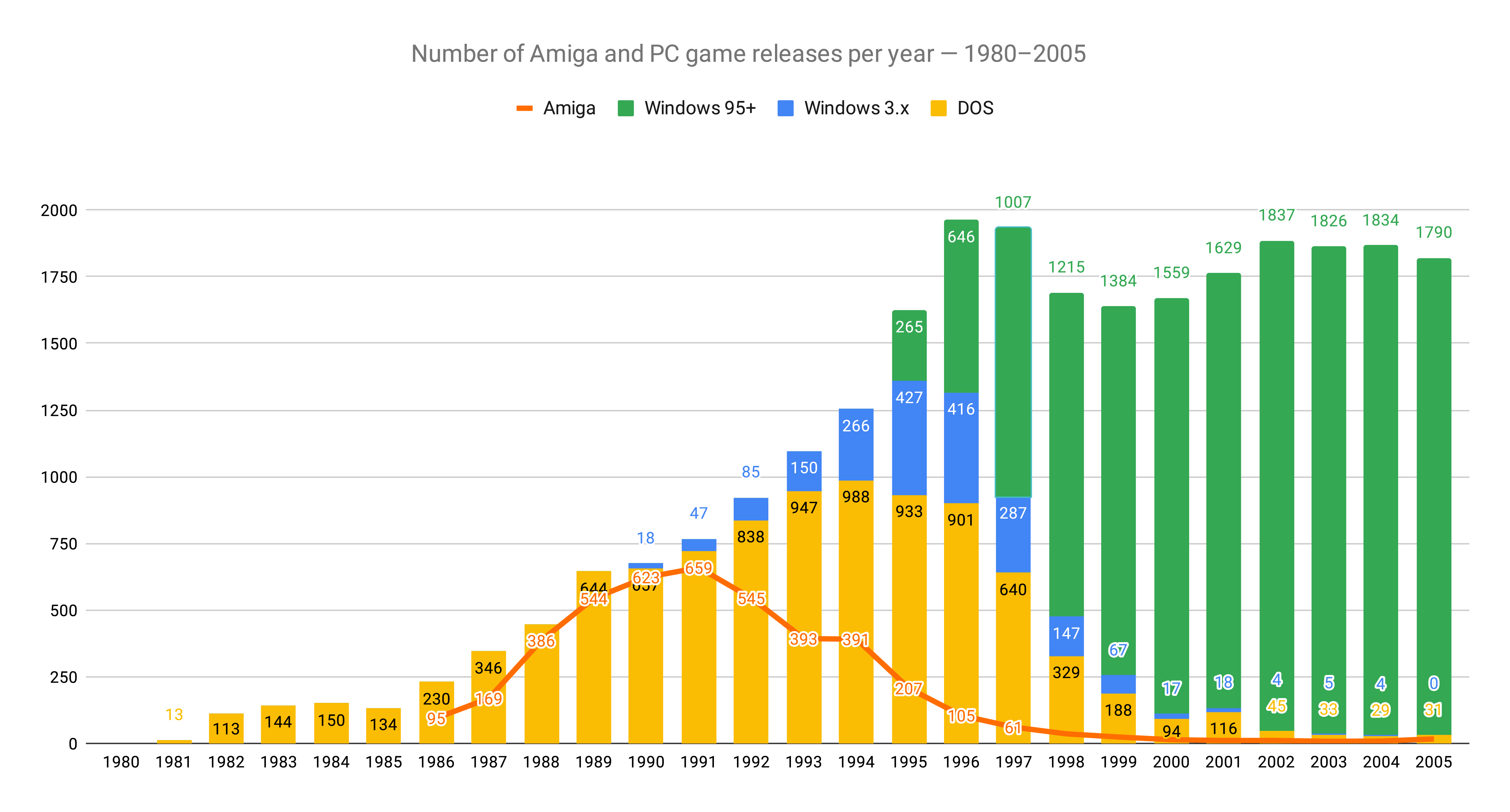

The below charts generated from data provided by MobyGames illustrate quite well the fast-paced nature of technology adoption in IBM PC games around the end of the 80s. MS-DOS as a gaming platform was going forward at a steady pace like a Sherman tank; one had to be blind not to see the writing on the wall (and you can be sure this trend didn’t go unnoticed by all those financial analysts working at larger American game companies).

All in all, while the Amiga 1000 and 500 were revolutionary at their inception, the Amiga 1200 offered only a rather modest evolutionary upgrade to those classic machines, and overall was a disappointment. It was too little and far too late. Naturally, there are long forum threads discussing this in painstaking detail, with lots of zealotry, name-calling, emotions running mile high, and—surprisingly!—even the occasional valuable insight and factual information can be found there if you’re persistent enough (I couldn’t muster up the strength to get past the 21st page myself in that linked thread…) My feelings about the eventual death-spiral of the Amiga and the general incompetency of Commodore management is summed up pretty well in this comment:

I was disappointed, but it’s like being disappointed with one of your family; you ignore the negatives and love it anyway.

Just as a brilliant but lazy student would be eventually overtaken by his less bright but diligent peers, the groundbreaking design of the Amiga 1000 alone couldn’t maintain the Amiga’s status forever as the best multimedia computer without major ongoing innovations. It almost feels like betrayal posting the below chart, but that’s the sad reality for you—in the end, the comparatively crude PC architecture, brute force, and the vast armies of industrious PC clone manufacturers from Asia had won the battle.

OCS vs AGA

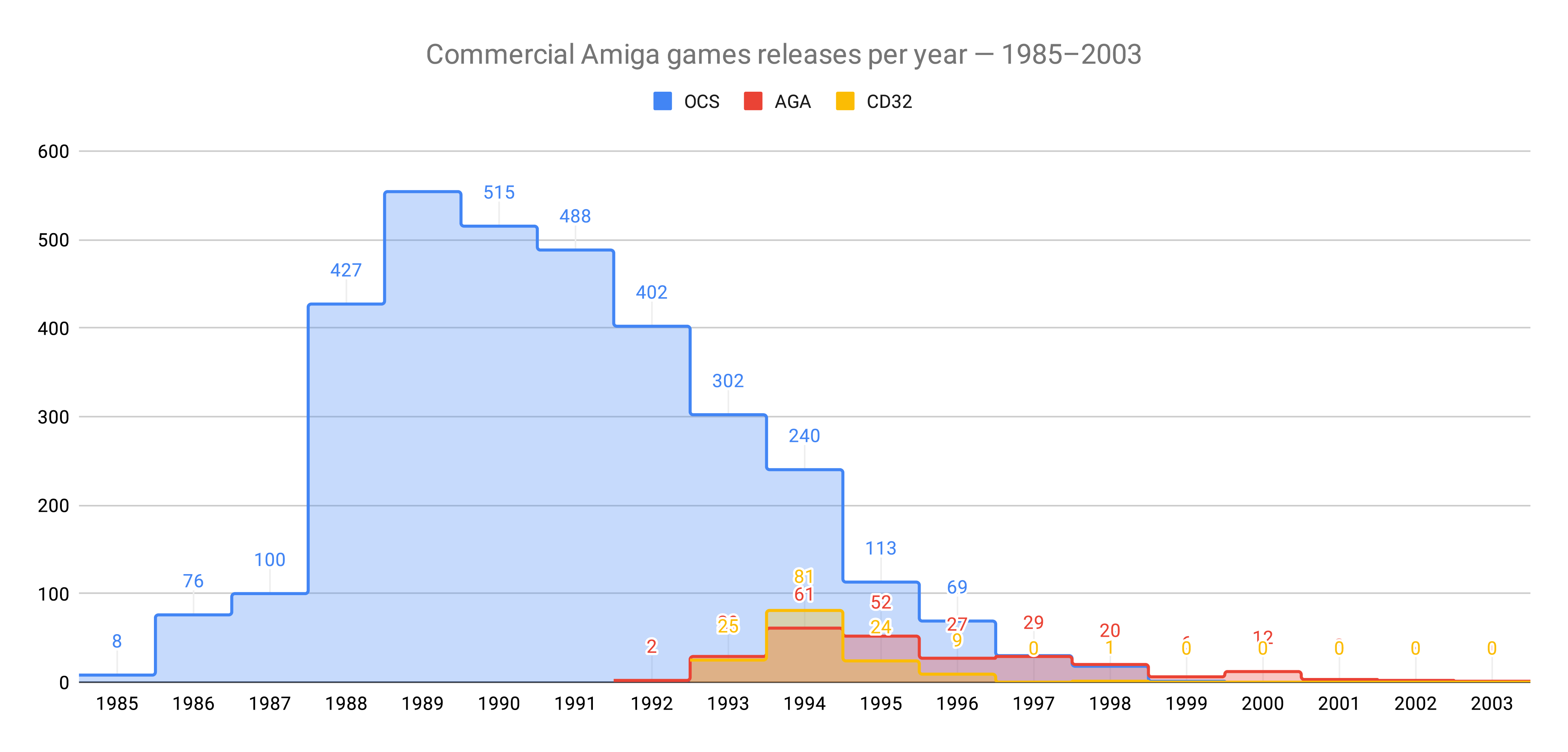

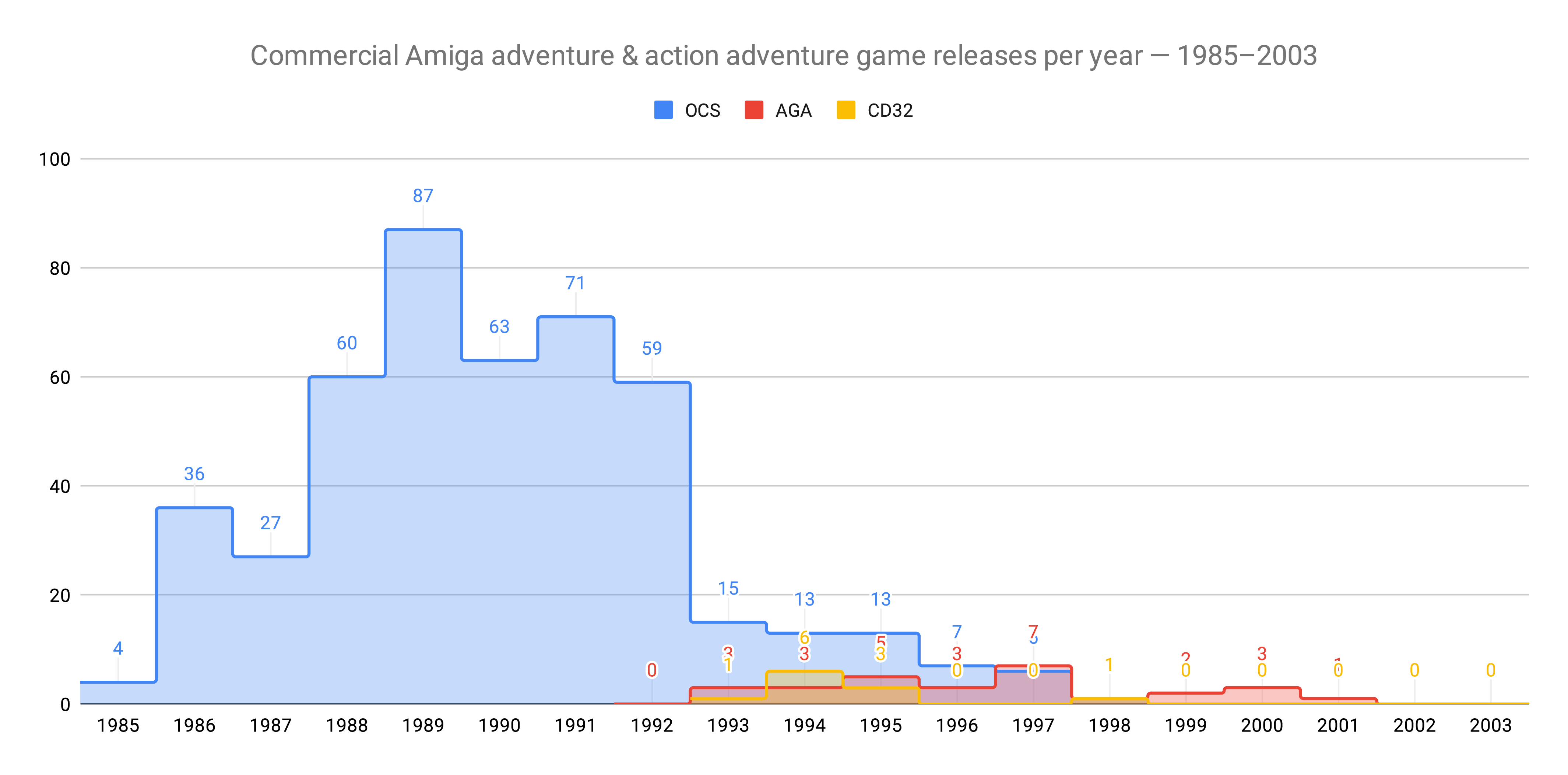

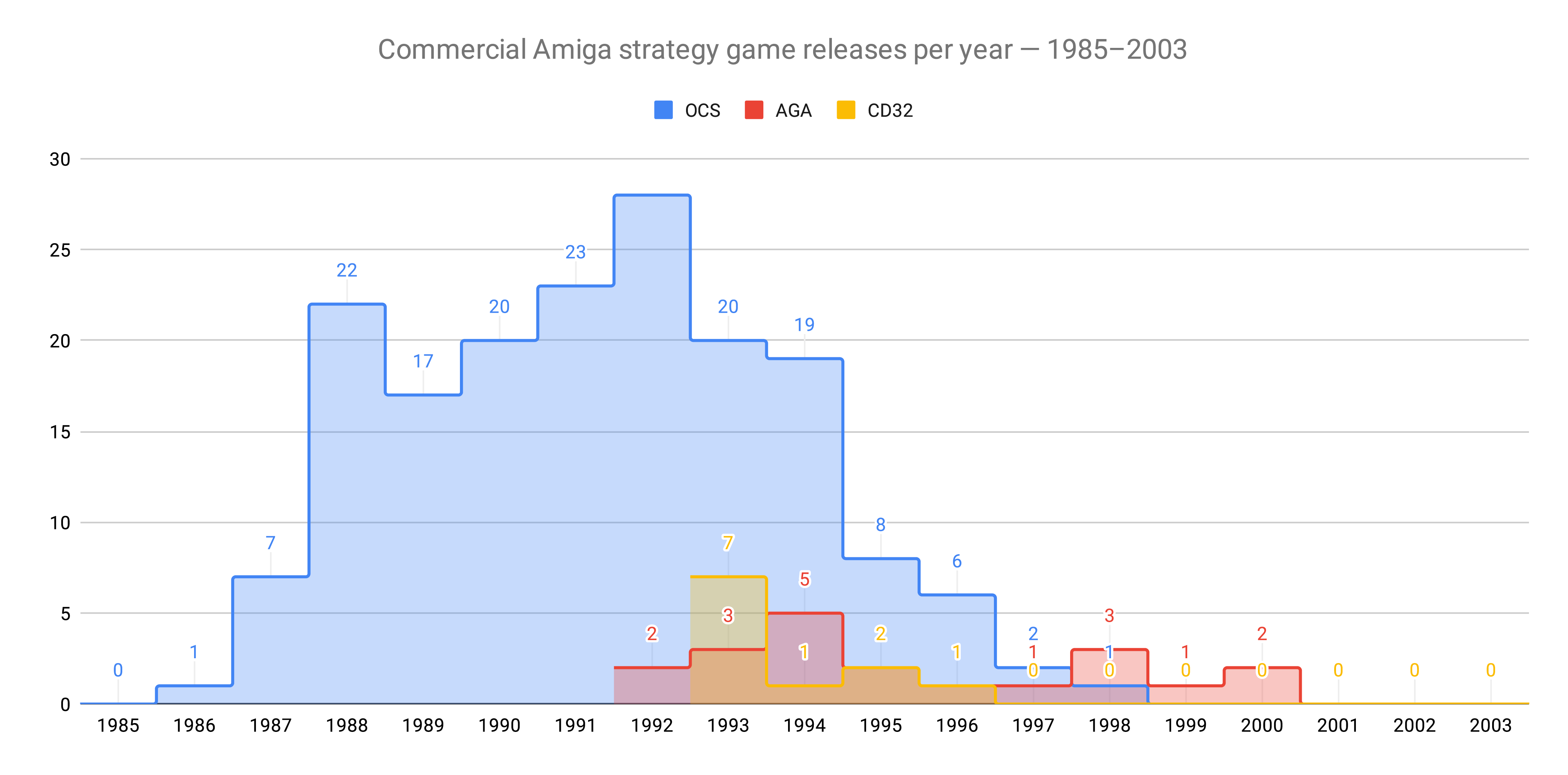

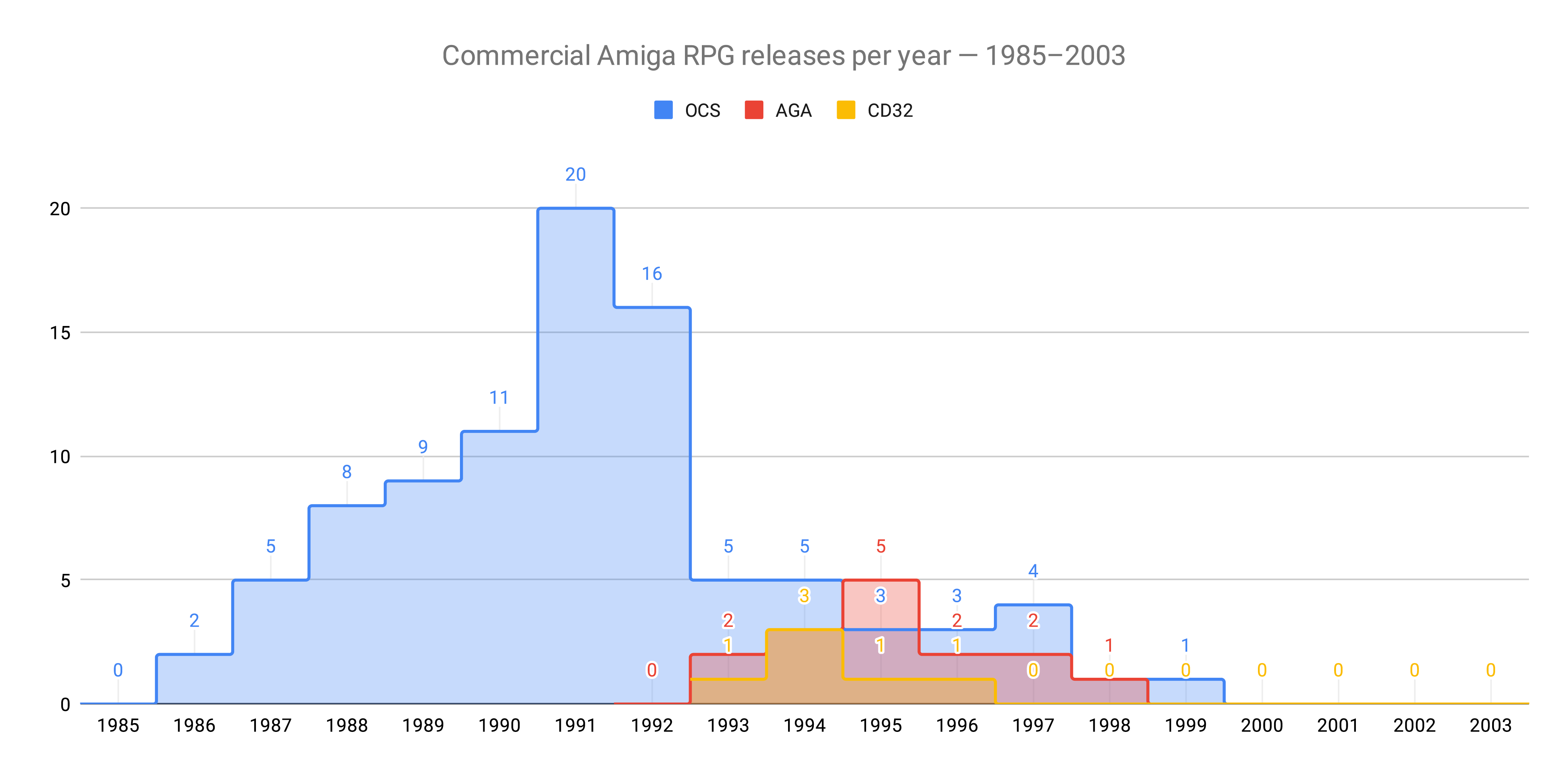

The relative importance of the AGA architecture is a source of endless debates in Amiga circles. But let’s sidestep that and have a look at some actual numbers instead! Thanks to the Hall of Light online database, I was able to collect some statistics on the number of commercially released Amiga games—looking at the OCS and AGA numbers separately is pretty revealing. I’ve included the CD32 as well; although it was basically an Amiga 1200 with a CD-ROM (plus the vastly underutilised Akiko chip), I think it warrants its own category. You can check out the raw numbers and the database queries I used here.

As we can see, the total number of AGA and CD32 games dwindle in comparison to OCS:

The chart quite nicely illustrates that gaming on the Amiga started in earnest in 1988, a year after the affordable Amiga 500 came out. There was a golden-age period until about 1991/92, after which the number of releases plummeted due to the increasing popularity of DOS gaming. The release of the AGA architecture could not reverse this trend; the Amiga 1200 did not sell that well, and quite understandably, developers were reluctant to target anything else than the least common dominator, which was still the Amiga 500. The decline continued until the eventual bankruptcy of Commodore in 1994, after which things took an even sharper downward turn. It takes a lot of goodwill not to declare the Amiga officially dead as a mainstream gaming platform by 1995.

These numbers actually put AGA releases into a much better light because most of them were in fact just rehashes (read: cash-grabs) of earlier OCS games with minor graphical upgrades. Many people (me included) think the OCS originals have more character and are thus the definitive versions. Another sizable chuck of the AGA releases were phoned-in ports of DOS VGA games. Sure, back in the day every Amiga owner was happy for whatever they could still get for their beloved aging platform, but there’s very little sense in preferring these lackluster ports to the genuine articles today (apart from historical interest, perhaps), which are the DOS originals.

I am personally not interested in action games much (apart from classic action-adventures, such as Another World, Flashback, Rick Dangerous or Prince or Persia which require some thinking in addition to quick reflexes), so let’s take a closer look at my favourite genres: adventures, strategy games, and RPGs.

There are a handful of AGA ports with better music on the Amiga, and there are the AGA/CD32 exclusives, but both pools are pretty small. So small that I’ll list every single adventure, RPG, and strategy game that falls into these special categories and are worth playing on the Amiga in my view.

But first, let’s look at the general trends:

No big surprises here, but it’s quite interesting to see the abrupt drop in the number of new releases in 1993 in both the adventure and RPG categories. My guess is that this is the result of major American developers seeing the writing on the wall and abandoning the platform (a significant portion of the more cerebral Amiga titles were American-made).

Finally, here are the results in numeric format:

| Percentage | All | OCS | AGA | CD32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All genres | 100.0% | 89.7% | 6.5% | 3.8% |

| Adventure | 13.4% | 12.4% | 0.8% | 0.3% |

| Strategy | 5.5% | 4.7% | 0.5% | 0.3% |

| RPG | 3.1% | 2.5% | 0.4% | 0.2% |

| Totals | All | OCS | AGA | CD32 |

| All genres | 3727 | 3343 | 244 | 140 |

| Adventure | 501 | 462 | 28 | 11 |

| Strategy | 205 | 174 | 20 | 11 |

| RPG | 114 | 93 | 15 | 6 |

Non-OCS adventure, RPG, and strategy games worth playing

Okay, so we have unequivocally established that the target platform for the overwhelming majority of the Amiga gaming catalogue is the Amiga 500 with the OCS chipset. But let’s have a look at the aforementioned small pool of non-OCS titles that are still worthwhile to play on the Amiga—these account for the “(mostly)” part in the title.

All these games have either official HD installers, can be manually installed onto the hard drive (e.g. Ishar I), or exist as CD32 games where you just pop in the CD and off you go. So neither of them requires WHDLoad or would be improved by WHDLoad in any way.

Again, focusing on adventures, RPGs, and strategy games. I don’t care about pure action and shoot’em up stuff, and you really have to be a masochist to play Amiga ports of VGA era flight and space simulators 😎

AGA/CD32 versions of DOS VGA games

Although the below games do have very respectable DOS versions, their Amiga ports offer something unique (usually in the sound department), making them the preferred option for the true Amiga aficionado:

- Beneath A Steel Sky (CD32; although the Amiga version has less colours, it’s a skillful conversion, and I much prefer the atmosphere of the slightly grungy Amiga soundtrack)

- DreamWeb (AGA; that’s the uncensored Amiga original, and it has better music)

- Eye of the Beholder I, II (AGA; the definitive fan-made AGA version that combines the superior sound of the Amiga ports with the original 256-colour VGA graphics, plus includes the Amiga-only outro sequence of the first game, which was cut from the DOS original)

- Inherit the Earth (AGA, CD32; I prefer the music in the recently discovered lost English beta version that is completable with minor bugs)

- Ishar I, II, III (AGA; the music is completely different and better in the Amiga versions)

- Simon the Sorcerer (AGA, CD32; better music on the Amiga, the CD32 version even has voice-acting)

- UFO: Enemy Unknown (AGA, CD32; the music of the Amiga version was done by the legendary scene musician, 4mat, therefore many people prefer this to the DOS original that has a completely different soundtrack. Requires a fast expanded machine to play at acceptable speed.)

AGA/CD32 exclusive adventure games

You can only play these on the Amiga—there are no other options:

- Sixth Sense Investigations (AGA, CD32)

- Wasted Dreams (AGA)

- onEscapee (AGA; Flashback style action adventure)

AGA/CD32 exclusive RPGs

As above; no Amiga equals no game for these:

- Evil’s Doom (AGA; never released officially)

- Liberation: Captive II (AGA, CD32)

- The Speris Legacy (AGA, CD32; an underwhelming Zelda clone)

- Trapped, Trapped 2 (AGA; requires a fast expanded machine to play at acceptable speed)

AGA exclusive strategy games

Slim pickings, as all important strategy games were pretty much PC exclusives at this point:

- Foundation, Foundation: Gold, Foundation: The Directors Cut (spiritual successor of The Settlers)

- Total Chaos: Battle At The Frontier Of Time (shareware)

The case against WHDLoad

First, let me quote what Wikipedia’s has to say about WHDLoad because it’s rather well-written:

The primary reason for this loader is that a large number of computer games for the Amiga don’t properly interact with the AmigaOS operating system, but instead run directly on the Amiga hardware, making assumptions about specific control registers, memory locations, etc. The hardware of newer Amiga models had been greatly revised, causing these assumptions to break when trying to run the same games on newer hardware, and vice versa with newer games on older hardware. WHDLoad provides a way to install such games on an AmigaOS-compatible hard drive and run on newer hardware. An added benefit is the avoidance of loading times and disk swaps, because everything the game needs is stored on the hard drive.

Basically, people got fed up with the fact that they couldn’t play some of their old Amiga 500 OCS games on their new AGA machines and came up with a solution around 1996, which was WHDLoad. The added benefit was that it also allowed running the supported games from the hard drive. Keep in mind that most people sold their old Amiga 500 and put the money towards buying an Amiga 1200, so for many, this was the only option to play those old games.

So far, so good—what’s not to like? Quite a few things, actually. In order to work its magic, every supported game needs a so-called WHDLoad “slave” written for it that can perform a number of interesting (and complex) things:

Patch the game code, so it runs correctly (or rather, with minimal issues) on the AGA chipset with fast memory present and on faster processors (68020 at 14 MHz is the minimum for an A1200). This sounds like a good thing, but it’s not always possible to do 100% perfectly for all games, resulting in sync and timing issues. Also, if not all of these incompatibilities have been patched up, that can result in bugs or crashes. But that’s just the nature of the beast; you need to trust the author of the WHDLoad slave if you’re going down this route. You’re not just dealing with the original game code anymore, but an additional layer on top of that.

Emulate the environment the game expects, for example, an older Kickstart version or some specific memory layout. Many older, OS-unfriendly games expect a fixed memory layout (e.g. a stock A500 with the extra 512 KB slow RAM), and would crash on any other setup. So the slave needs to emulate the old Kickstart in software and do various magical things to fool the game into believing it runs from a floppy on a, say stock Amiga 500 with Kickstart 1.2. All these machinations require extra memory; in fact, only a few WHDLoad games can run on a stock A1200 with 2 MB chip RAM. At least 8 MB fast RAM is recommended, but preferably more. This is not a big deal when using an emulator, but… I just don’t like it. It’s too much complexity; there’s so much room for things to go wrong compared to a simple Amiga 500 setup the game was coded for (but I admit, all this machinery is very cool from a purely technical point of view).

Allow high-scores and save games to be stored on the hard drive. Again, a cool feature on paper, but many of these games could only store such data on floppies, often bypassing the OS completely. So the game needs to be patched to write this data into some temporary buffer in memory, then when the buffer fills up, AmigaOS needs to be swapped back into the memory space now occupied by the game to be able to write the buffer to disk (it’s not possible to access the hard drive without the OS, and many older floppy games start by killing the OS right away). Then the game code needs to be swapped back, and this goes back and forth for a while. Usually this results in a black screen, and it can slow things down quite a bit (it’s referred to as “OS swapping”). Some slaves only perform the writes when exiting the game, presumably as an attempt to minimise the number of OS swaps required, but if you forget to properly quit the game using the WHDLoad “quit key”, or worse, the game crashes on you, all your saved (!) progress from your session is lost… I think this is the #1 issue that gets every WHDLoad newbie, and I certainly did lose my progress more than once by forgetting to quit the game via the quit key. Although I’m not 100% certain about the technical explanation, such slowdowns can also affect games that perform lots of reads during the game, often slowing them down 2 to 5-fold! Sometimes the WHDLoad version runs slower than the floppy version (!), which I find plain unacceptable.

Remove copy protection from games that use nefarious disk-based protection schemes and/or custom non-DOS disk formats. Although the majority of WHDLoad conversions require original uncracked floppy images, removing such protections is a necessity and effectively requires the slave author to crack the game. Sure, not having to consult code wheels and manuals sounds like an improvement, but this comes with all the drawbacks associated with cracking—a bad crack can simply render the game unplayable. This is certainly annoying in action games and platformers that take a few hours tops to finish (and therefore are easy to test by the crackers), but in the case of adventure games, and especially RPGs that can take anywhere between 20 and 100 hours to complete, a bad crack can be catastrophic. Some devious developers had literally woven the protection into the fabric of the game’s code; it wasn’t just a simple question/response style manual or code wheel check at the beginning, but the protection was embedded into the game, so to speak. Moreover, there was no indication whatsoever of failing these subtle checks, the game did not outright stop or crash but let you keep playing for hours on end while gradually crippling the experience until it got into an unwinnable state, possibly even corrupting or “infecting” your save files. Needless to say, very few crackers had spent 20-100 hours completing such games over and over to test their cracks (just think of a complex branching RPG and how much effort it would be to test that properly). Here’s a few notable examples:

Fate: Gates of Dawn, one of the longest and best Amiga-exclusive RPGs:

It is notable that from these copies of the game only the copy protection but not the password protection was removed. Password requests are not made at the start of the game but at intervals in the game repeated after some time. Just ignoring these requests or a wrong answer leads not to an abrupt end to the game, but gameplay deteriorating until it becomes unplayable. Therefore, a copy of the manual is still required for the right code.

The ingenious protection scheme of Dungeon Master had received a lot of respect from crackers back in the day; it took them a year to fully reverse engineer it. The protection definitely served its purpose in this particular case!

Additional anti-piracy checks exist in the code, including further fuzzy bit sector reading, checksums, code hidden as images in GRAPHICS.DAT, and other fun tricks intended to slow down and frustrate crackers. These respond with a delay-action effect […] It is still possible to complete the game if you save progress frequently. These checks only hinder progress rather than making the game impossible.

This commenter is probably reminiscing about the copy protection of Dragonflight:

There was an Amiga RPG, I think by Thalion that made the game crash when the anti piracy was triggered. However some time later there appeared a full screen stylized pirate skull over whatever game you had running then. This was kind of scary because we thought it was some virus until we realized it was the RPG game that keept the skull in RAM even after a reset until you turned off your Amiga.

Not an Amiga game, but an interesting case nonetheless:

Another copy-protection classic was Spyro: Year of the Dragon: https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/keeping-the-pirates-at-bay

This used a multi-layered copy protection scheme. The first layers would show a dialog and quit. Later layers got progressively more vicious:

- They’d remove 1 out of 10 gems needed to complete a certain level.

- They’d randomly corrupt data.

- They’d change the UI language at runtime.

Read the post-mortem I linked above; it’s really fun. The basic idea was to require crackers to play the entire game very carefully, looking for subtle side effects that broke game play.

Okay, so you get the picture. I’m not saying all cracks are bad, but quite a few were back in the day; I clearly remember that. If you were unlucky and got your hands on a bad crack of a long adventure game or RPG, you just had to put it aside until you managed to find a working crack. The thing is, it doesn’t really matter if 50% of cracks are bad or only 1%—you have no way of knowing beforehand whether a particular game is affected or not. So you can either do an extensive online research first and hope the answers you find are accurate, or just resort to playing uncracked originals. Personally, I very much recommend the latter unless there’s no other choice but to play a cracked version.

Here are some concrete problems I’ve encountered with WHDLoad games. Note that I wasn’t looking particularly hard to find faulty slaves; I just installed a bunch of my favourite games and about half of the time I had run into some weirdness or suboptimal behaviour. That’s surely annoying for me who knows how these games should play, but it can certainly put someone off for good from Amiga gaming entirely who is new to it and doesn’t know any better. That is one of my biggest problems with WHDLoad being recommended everywhere as the ultimate magic solution—it’s cool, it’s clever, it might even work well with some particular games, but it’s most certainly not the best solution for many games, it’s not the authentic experience, and it simply puts many classic Amiga games in a bad light.

Alright, so here we go:

Ishar III AGA: Opening the map takes 4 seconds, and closing it around 13 seconds (!) in the WHDLoad version. This makes the map completely unusable! Bumping up the CPU speed to a 50 MHz 020 reduces the wait times by about 40%, but it’s still slow. Whereas when playing the game from floppies or using the included HD installer, opening the map is almost instantaneous, and closing it takes less then 2 seconds with the stock 14 MHz 020 CPU, which is perfectly usable. Because the game contains an HD installer on the first disk, it’s a bit perplexing why a WHDLoad version even exists in the first place… (well, I know the answer: because of the “trainers”—which is another thing I recommend against).

Pool of Radiance: Saving the game into a new slot takes more than a minute (!), during which the screen is mostly black (OS swap, a common theme with many WHDLoad games). Of course, saving goes swiftly if you play the game from the hard drive on an Amiga 500 (HD installer is on the first disk).

Lemmings: The game freezes randomly after about 10-30 minutes of playing (most likely due to an incomplete crack). To my knowledge, the issue hasn’t been rectified as of 2022, which is a shame for such a classic title.

King’s Bounty: Severe slowdowns, probably due OS swapping. Timings when playing the game on a stock Amiga 500 with the manual HD install method:

- creating a new character – 47s

- opening the Puzzle Map – 5s

- closing the Puzzle Map – 2s

And the WHDLoad timings on a stock Amiga 1200 with 128 MB of RAM (!):

- creating a new character – 116s (2.5x slower)

- opening the Puzzle Map – 23s (4.6x slower)

- closing the Puzzle Map – 8s (4x slower)

Certain actions in the WHDLoad version are just unacceptably slow! It doesn’t matter how much extra RAM you have; these actions will takes ages every single time. And these are not the only ones; there’s a lot more (e.g. when saving the game)—I just didn’t bother measuring them all…

Warhead: Saving the game takes a long time, and the screen keeps flashing (OS swap).

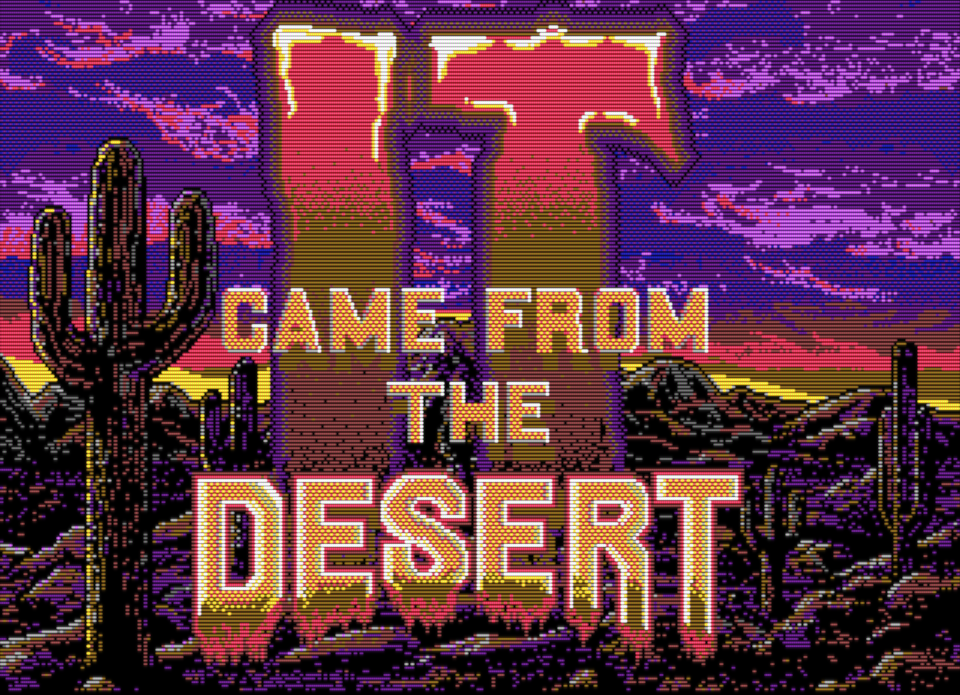

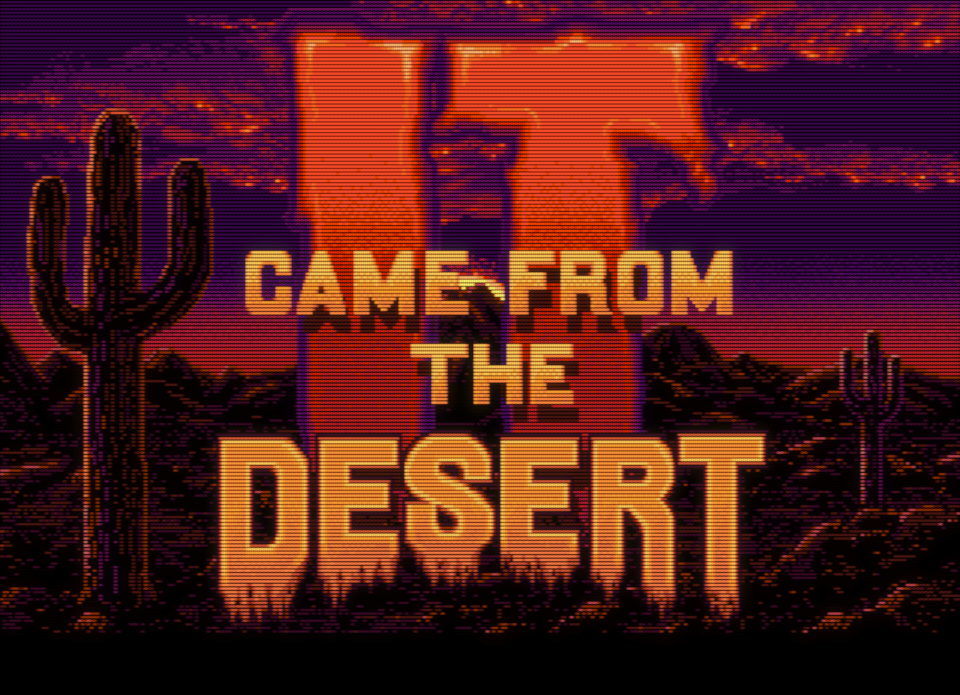

It Came From the Desert: Speed and music syncing problems (the music gets cut off before the intro can properly end).

As you would expect, all these games work perfectly fine and without any issues when run from the hard drive or floppies on an Amiga 500 (you need an A1200 for Ishar III AGA, of course).

Amiga configurations to play all games

So, from all the above we can conclude that to be able to play all Amiga games worth playing, we’ll need three base configurations:

- Amiga 500 with hard drive

- This setup will take care of the vast majority of your gaming needs:

- All OCS games that have official HD installers:

- Most games made by North American studios (e.g. LucasArts, SSI, Sierra, Interplay, Infocom, MicroProse, Cinemaware, Dynamix, SSI, Westwood, New World Computing, Maxis, etc.)

- Most adventures, RPGs, and many strategy games made by European studios (e.g. Bullfrog, Coktel Vision, reLine, HorrorSoft / Adventure Soft, Delphine, Magnetic Scrolls, Level 9, Thalion, Revolution, Silmarils, etc.)

- Many OCS games that do not have HD installers, but can be installed onto the hard drive manually quite easily (e.g. MicroMagic games)

- OCS games that can only be run from floppies (and there are a few tricks to speed up loading times, too, as we’ll see)

- All OCS games that have official HD installers:

- Amiga 1200 with hard drive

- For the handful of AGA games, which all are HD-installable (as per above)

- The even smaller pool of games where you’re better off with WHDLoad:

- Fate: Gates of Dawn (patched English version with restored nudity from the German original; confirmed to be completable)

- Eye of the Beholder AGA I, II (fan-made port of the DOS VGA original with superior Amiga sound; these only exist as WHDLoad games, they’re very well done and completable)

- Where Time Stood Still (fan-made port of the Atari ST game)

- Amiga CD32

- For the odd CD32 game

Alright, this will do as a proper introduction to the subject. In the next episode, we’ll look at floppy games and how to play them like a man (or perhaps a woman) of culture! 😎

References & further reading

Yes, many games do actually display a lot more colours on the screen at once by using bobs, sprites, splits screens, copper tricks, etc. I’m just talking about the standard screen modes here. ↩︎

Comments

comments powered by Disqus